My site-mate, Kelly, recently made a connection with a woman from Chicago named Helen who is working on clean water solutions for Guinea. Her connection to Guinea is through an artist named Fode Camara. Fode happens to be from the same village we are working in — Koba!

The world is funny and small.

This weird chain of connections led to this weekend. Me, Kelly, and Christine (another volunteer in the nearby area) traveled to Conakry this weekend to Fode’s house to learn how to make a biosand filter. Kelly was heavily involved in Engineers Without Borders when she was in college and actually made the same exact filter in El Salvador.

Did I mention how funny and small the world is?

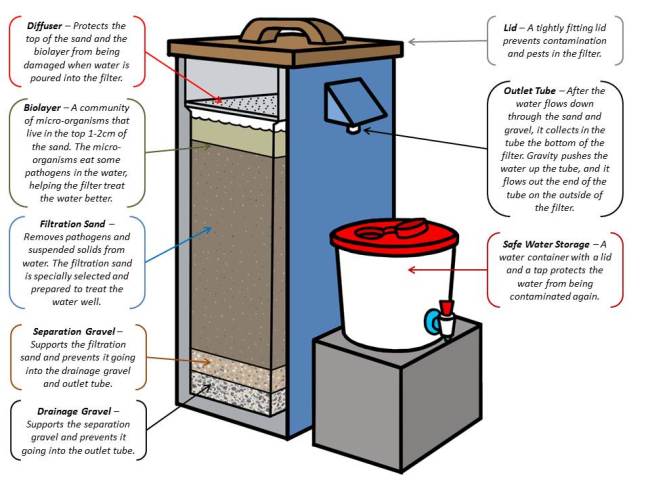

Biosand filters work by using a column of gravel and sand with a biofilm to filter water. In the field they have been shown to remove 70 – 80% of heavy metals, turbidity, bacteria, viruses, and protozoa. The model Fode and Helen use was designed by the Center for Affordable Water and Sanitation Technology — check out their website here for more information on the engineering and science behind these filters. Here’s a quick run-down:

So, we made one this morning. Fode already has a mold made, so all we had to do was purchase a bag of cement for 70,000 FG — $10 USD. This is enough cement to fabricate two filters. Factoring in the other costs — making the lid, the basin, the plastic hose, and the sand and gravel — I am guesstimating that the total cost for one of these filters is $10-15 USD. And it lasts a life time.

The mold, however, is the problem. It can cost between $1,000 to $2,000 USD to make. But Fode has made 63 filters using his mold so far, and they are working on more every day. It took us about 1 hour to make the filter, and then it takes 24 hours to dry in the mold.

Here is the mold:

Mixing cement:

Pouring the cement into the filter. You have to beat the side of the mold and simultaneously push the cement down to insure that no air bubbles are trapped inside. The air bubbles would cause the mold to crack later on after it has dried:

Here is a finished filter that they made the previous day:

A close up of the drainage basin — this is in place so as to not disturb the sand when you pour water into the filter:

After we made the filter we talked for a little bit. As I mentioned, Fode and his crew have already made 63 of these filters and distributed them throughout their community in Conakry. I wanted to see them in action so we walked around and visited about 15 of the nearby houses who had filters. All but one were using them and loving them. Fode said he will return to the one that wasn’t using it tomorrow and if it is still dry, he will take it and give it to a family that wants it. While we were walking around, several people stopped us and asked Fode when they could get a filter of their own.

So. We are looking at an expensive start-up cost with inexpensive routine costs. In the coming weeks and months Kelly and I are going to move forward with this project — finding grant funding (and calling on friends and family from home to fund the project), figuring out the best way to implement it into Koba and possibly Basse Cote at large, how much people can afford to pay for one (because giving them away for free will not foster a sense of responsibility and ownership), who will get the first ones (because Guineans are very jealous), how to educate people about the importance of clean water, etc etc etc. I am very excited and so inspired by Helen and Fode’s actions I almost cannot find the words to express it.

Big things are coming to Koba.